[Mirror] BitTorrent client case study

Note: This is a mirrored version of a GitHub post by Michael Parker. Trevor Blackwell in his FAQs recommends Bittorrent as a good codebase to read.

Just as there is a wide gulf between answering an interview question on a whiteboard and delivering an app to your users, so there is a wide gulf between dissecting design principles in isolated examples and employing those same principles in real, shipping code. To demonstrate these principles in the latter context, I sought out a medium-sized, well architected, and historically significant open source application. Eventually I chose the peer-to-peer application BitTorrent, also known as the “mainline” client of the BitTorrent protocol.

Bram Cohen released the first version of the mainline client and the BitTorrent protocol specification in 2001. Below we examine version 3.4.2 of the client, which is written in Python and was released in 2004. It is the last version released under the permissive MIT license, and is also the last version available through the dormant SourceForge repository. Since this time the BitTorrent client has been closed source; currently it extends the μTorrent client.

While this code is over 10 years old, this chapter will demonstrate that its robust design makes it exceptionally readable and understandable. It still exemplifies many important facets in design, such as encapsulation, abstraction, decomposition, and more. If you want to explore the code more thoroughly, I’ve pushed a fully commented version of it to GitHub.

Protocol description

Before exploring the design of the mainline client, we must understand the underlying BitTorrent protocol. The majority of this understanding comes from the BitTorrent protocol 1.0 specification and archived mailing list discussions. Let’s start by defining four basic terms:

- A torrent is a set of one or more files that clients download.

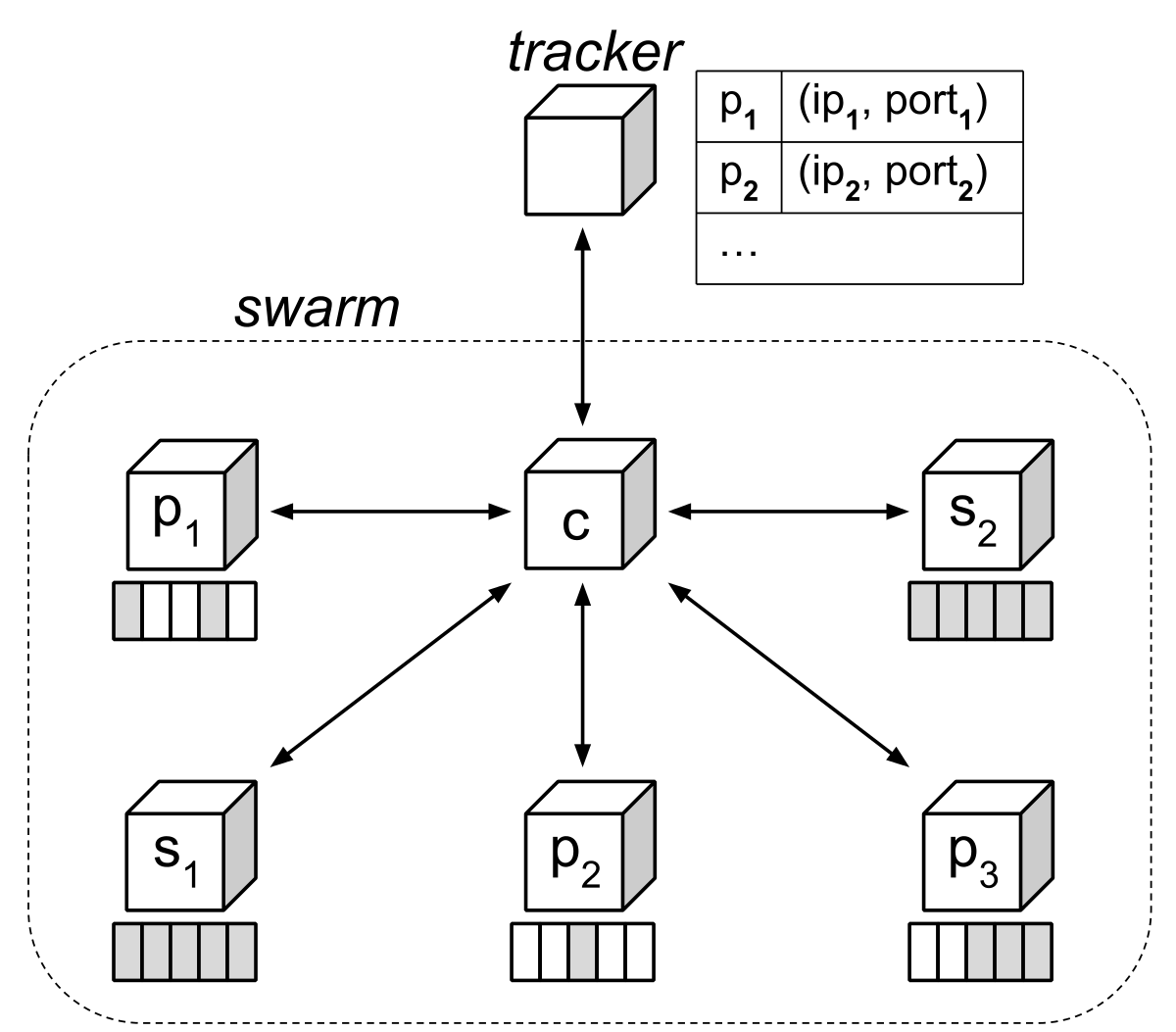

- A swarm is a set of BitTorrent clients that exchange data belonging to a torrent.

- A peer is any BitTorrent client participating in a swarm.

- A seed is another name for a peer that has completed downloading a torrent.

Below, the client refers to the locally running BitTorrent client, and its peers refer to only those peers that the client is connected to. Again, such a peer may or may not have completed the torrent, unless we explicitly call it a seed.

Metainfo file

A client starts by downloading a metainfo file, which typically has the file extension .torrent. This file contains two important data items:

File descriptions

First, the metainfo file contains a dictionary structure that describes the files in the torrent. It pairs the relative path of each file with its length in bytes. By adding together the lengths of all the files, a client can compute the total number of bytes in the torrent.

It’s important that a client verifies the integrity of data that it downloads from its peers. Unlike an authoritative website serving a download over HTTP, any peer could be malicious and send junk data to the client. If BitTorrent used just a single hash to verify the integrity of the entire torrent, then a malicious peer could corrupt the download of the client by changing just a single byte. The client would then need to download the entire torrent again, consuming significant additional time and bandwidth.

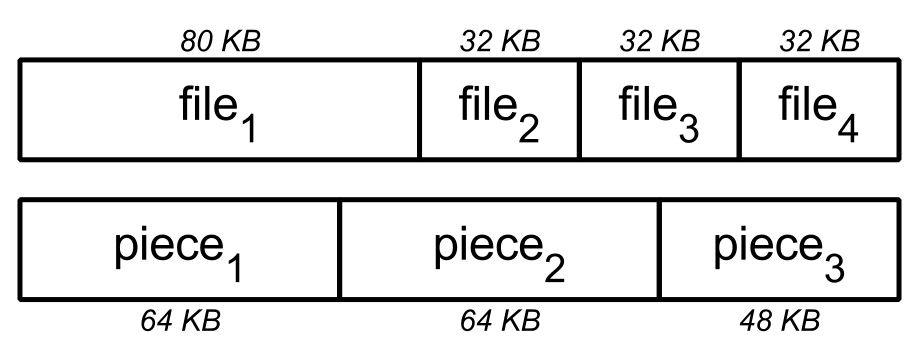

To guard against this, the metainfo file specifies a positive piece size that divides the torrent into pieces. All pieces preceding the last piece are this size. If the piece size does not divide evenly into the total size of the torrent, then the last piece is a smaller, positive size. The metainfo file also specifies the SHA-1 hash of each piece. When a client downloads a piece from a peer, it computes the SHA-1 hash of that piece, and then compares its value against the expected value from the metainfo file. If they differ, then the client can blacklist that peer, and then download the piece again from a different peer. This way a malicious peer can only corrupt the download of a single piece. That peer cannot corrupt the download of the entire torrent.

Tracker announce URL

Second, the metainfo file contains the announce URL of the tracker. The tracker is a web service that listens at this URL for HTTP or HTTPS requests from peers. Peers periodically “announce” to the tracker that they are participating in the swarm.

Each announcement by a client includes how many bytes it has downloaded and uploaded, and how much of the torrent it has yet to download. This lets the tracker assess the overall “health” of the torrent. For example, the swarm of an unhealthy torrent could consist of only one peer that is not a seed. That peer can only complete downloading the torrent if another peer with the missing data joins the swarm. By contrast, the swarm of a healthy torrent could consist of a hundred seeds. A new peer that joins the swarm can completely download the torrent from any one of these seeds.

Each announcement by a client also includes a unique identifier, along with the IP address and port number on which it listens for incoming connections by peers. This lets the tracker build a list of all clients participating in the swarm. If the client sends an announcement to the tracker with the query parameter numwant, then the tracker replies with the IP addresses and port numbers of other peers in the swarm. This is how the client finds peers to connect to and exchange data with.

Bencoding

The contents of the metainfo file are encoded using bencoding. Like JSON or YAML, it can encode any hierarchy of strings, integers, lists, and dictionaries. But unlike JSON or YAML, it encodes strings as length-prefixed byte strings. For example, the following bencodes the string "bittorrent":

10:bittorrent

Bencoding therefore allows embedding binary data verbatim instead of resorting to base64 or an alternative textual representation. Because the SHA-1 hashes of the pieces constitute the majority of the metainfo file, this significantly reduces its size.

Piece picking

As we will explore in detail below, a client knows which pieces each of its peers have. If n of its peers have a piece, then the availability of that piece is n. A client cannot completely download a torrent if some piece that it has not yet downloaded has an availability of 0. Therefore a client prioritizes downloading from its peers the pieces with the lowest availability. This is known as the rarest first piece picking strategy. It increases the availability of the rarest pieces and minimizes the probability that they become missing when peers leave the swarm.

Choking

Peers connect to each another and exchange pieces of the torrent with each other. But a client can restrict a given peer from downloading data from it by choking that peer. Upon receiving a choke message from the client, the choked peer assumes that the client has discarded its outstanding requests for data, and that the client will ignore its future requests for data. The client can later unchoke the peer. Upon receiving an unchoke message from the client, the peer can resume requesting data from it. Consequently, a client will upload only to peers that it is not choking, and can download only from peers that are not choking it. More specifically:

- If peers A and B are not choking each other, then either peer can download data from the other one.

- If peer A is choking peer B, but peer B is not choking peer A, then peer A can download data from peer B, but not vice versa.

- If peers A and B are choking each other, then neither peer can download data from the other one.

Peers choke each other for two reasons:

- According to archived discussions on the BitTorrent mailing list, TCP congestion control performs poorly when many connections are active at once.

- This lets a client upload data quickly to a few peers, instead of slowly to many peers. An unchoked peer will complete downloading a piece faster, which in turn reduces the time until it can upload the piece to its own peers. This improves the health of the torrent.

The client’s strategy for choosing which peers to choke depends on whether it is a seed or not. If the client is a seed, then it unchokes the peers that it can upload to the fastest. Again, this minimizes the time until such a peer can upload the piece to its own peers. If a client is not a seed, then it unchokes the peers that it can download from the fastest. This is why BitTorrent is said to use a tit-for-tat algorithm. Moreover, this promotes Pareto efficiency, where two peers with fast connections will favor exchanging data with each other in order to maximize their combined benefit.

The client unchokes five peers. Four peers are the fastest ones that the client has found so far, and one peer is the optimistically unchoked peer. The client randomly selects this peer. After 30 seconds, the client chokes the slowest of these peers. It then chooses a new optimistically unchoked peer and the process repeats itself. By optimistically unchoking a randomly selected peer, the client can test whether a new peer is faster than any of the four fastest peers that it has found so far. If so, then that optimistically unchoked peer remains unchoked, and joins the four fastest peers.

Wire protocol

As mentioned earlier, the tracker returns to a client the IP addresses and port numbers of peers in the swarm. Upon establishing a TCP/IP connection to such a peer, the client sends its unique identifier and a bit field specifying which pieces it has. The peer then reciprocates by returning its own unique identifier and bit field. The client therefore knows which pieces each of its peers have.

Once this handshake completes, a client sends messages of the following types to its peers:

- Keep-alive messages, to notify a peer that the connection is inactive, but has not timed out.

- Choke and unchoke messages, as discussed previously.

- Have messages, to notify each of its peers that it has downloaded and verified the integrity of a given piece.

- Interested and uninterested messages. The client sends the former to a peer when that peer has a piece that the client is missing, and sends the latter to a peer when the client already has all the pieces that the peer has. If the client is uninterested in a peer, then that peer will choke the client, since the client cannot request missing data from it anyway.

- Block request messages, to request an interval of a piece from a peer if that peer is not choking the client. Later, that peer can respond with a piece message, which contains the requested interval of data.

A client does not perform a teardown sequence to complement the handshake sequence. To terminate a connection with a peer, it simply closes the socket.

Design features

As said earlier, properties of the design include encapsulation, abstraction, and decomposition. Let’s look at these properties and examine their beneficial effects.

Encapsulation

Encapsulating both logic and data allows code to be used in a variety of contexts. The command line parsing and networking modules stand out as ready for reuse in entirely different applications, while the piece picking and bencoding modules are ready for use by any module in the BitTorrent client. Let’s examine these modules, and the effects of their encapsulation:

The command line parser

The parseargs module contains a single method, also named parseargs. This method parses all command-line arguments and command-line options from a given argument vector. The first version of this module was written in 2001. Python 2.3 included the optparse module for argument vector parsing, but it was released later in 2003. The parseargs module does not hard-code each BitTorrent command-line option and its default value. Instead, the client passes these options to the parseargs method, along with the argument vector that it should parse.

For example, the following code parses the argument vector arg1 --opt1 val1 arg2. The default value for option opt1 is default1, and the default value for option opt2 is default2:

| |

When run, this prints:

| |

The returned args array contains the parsed command-line arguments arg1 and arg2. The returned opts dictionary maps command-line option opt1 to its parsed value val1, and maps command-line option opt2 to its default value default2.

Again, modern Python code would use either the optparse or argparse modules from Python’s standard library. But the parseargs method still exemplifies encapsulated code that is ready for use by any application.

The networking engine

The RawServer class implements the event-driven reactor pattern that is found in networking libraries like node.js, EventMachine, and Twisted. The Twisted framework is also written in Python, but it is a heavyweight framework that was only released in 2002.

A client first calls the bind method of RawServer to specify the port on which it should listen for incoming connections. The client then calls its listen_forever method to continuously loop until a thread-safe quit flag is set to True. On each iteration of the loop, method listen_forever executes any tasks scheduled to run before or at the current time, accepts any new incoming connections, and then processes any events on established connections.

The client configures the RawServer instance with an object named handler. This object implements callback methods that respond to events in the RawServer, thereby separating the application logic from reactor implementation. Whenever the client establishes an incoming or outgoing connection, reads new data from a connection, writes all pending data to a connection, or when a remote host closes its connection, the RawServer instance invokes the corresponding method on handler. It passes to this method a handle to the connection and any data related to the event. In reaction to an event, the callback can enqueue data for writing to a connection, close a connection, open a new connection, schedule a task to run at a given time, or shut down the RawServer entirely and thereby close all connections.

Again, because the methods of handler implement all the application logic, any application can use RawServer by defining its own handler implementation. For example, the following handler implementation accepts an incoming connection, writes the string "hello there stranger\n" to that connection, and then immediately quits:

| |

If we run this in one terminal window, then from another terminal window we can connect to it using netcat like so:

| |

Returning to the original terminal window, we find that the Python program has quit.

Modern Python code would either elect to use the select module from the Python standard framework, or a framework such as Twisted. But it is notable that we can so easily configure and use a RawServer instance today, thanks to its principled design.

The piece picker

The PiecePicker class, as its name implies, picks the next piece that a client should download from a peer. While the client uses Bitfield instances to track which pieces each peer has, the PiecePicker adds all of these bit fields together. It therefore knows how many peers have a given piece, or the availability of that piece, but it does not know which peers have it.

The got_have and lost_have methods of PiecePicker increment and decrement the availability of a given piece. When a peer delivers its bit field to the client during the handshake sequence, the client calls got_have with the index of every set bit in the bit field. It also calls got_have whenever it receives a have message from a peer. The client calls lost_have with the index of every set bit in a peer’s bit field when that peer disconnects. Finally, its next method picks the next piece that the client should download from a peer. It takes as another parameter a method that returns whether the peer has a given piece.

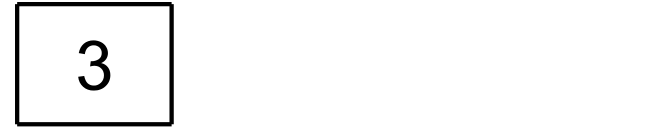

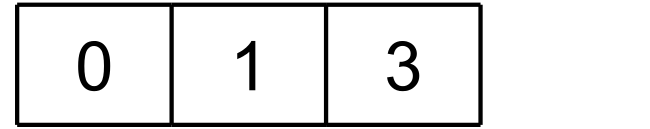

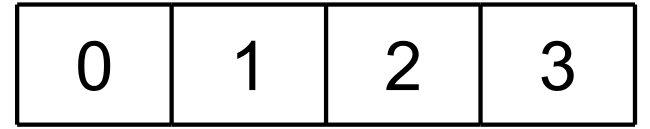

This design fully encapsulates the rarest-first piece picking strategy of the client. For example, the following code creates a PiecePicker with three pieces. Piece 0 has an availability of 3, piece 1 has an availability of 1, and piece 2 has an availability of 2:

| |

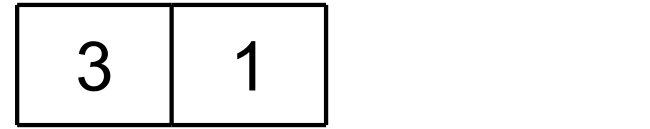

The PiecePicker instance can return the rarest piece to download from a seed, and the rarest piece to download from a peer missing piece 1:

| |

When run, this prints:

| |

It chooses to download piece 1 from the seed, which is the rarest piece. From the peer that is missing piece 1, it chooses to download piece 2, which is the second-rarest piece.

Other modules in the application can use the PiecePicker instance without even knowing what piece picking strategy it is using. Thanks to encapsulation, if we changed the strategy entirely, no code belonging to other modules would need to change.

Bencoding data

The bencode module converts between a bencoded string and its corresponding hierarchy of strings, integers, lists, and dictionaries. The following code demonstrates this conversion using the module’s bencode and bdecode methods:

| |

When run, this prints:

| |

Above, bdecoded_data contains the original data.

While the bencode and bdecode methods denote the type of data encoding and decoding, encapsulation insulates the client from the details of those operations. If those methods were named encode_for_wire and decode_from_wire, respectively, then again the encoding and decoding strategy could be changed without any other modules needing to change.

Abstraction

Many modules effectively use abstraction to reduce complexity. As we will see below, both the storage layer and message processor are decomposed into classes with differing levels of abstraction. Additionally, the networking engine creates a single abstraction for two system calls with different interfaces, thereby allowing one client to use either implementation. Finally, we will examine how a class that implements a bit field uses abstraction to move from a low-level implementation domain to a high-level problem domain.

The storage layer

The storage layer writes downloaded pieces to disk and verifies the integrity of each one. It consists of the Storage and StorageWrapper classes. A Storage instance presents a low level of abstraction based on intervals of bytes. A StorageWrapper instance, as its name implies, wraps the Storage instance. It presents a high level of abstraction based on pieces. Let’s consider each in turn.

Given the list of filenames and their associated sizes, a Storage instance calculates the first byte offset for each file. For example, below we construct a Storage instance with four files, where the first file is 80 bytes in size, and each of the remaining three files is 32 bytes in size:

| |

The Storage instance calculates the first byte offset of file_a as 0, that of file_b as 80, that of file_c as 80 + 32 = 112, and that of file_d as 80 + 32 + 32 = 144.

A private method _intervals uses the first byte offset and size of each file to find what file intervals span a given global offset and length in bytes. For example, below we call _intervals with a length of 64 bytes, and varying global offsets of 0, 64, and 128 bytes:

| |

When run, this prints:

| |

This means that:

- A global offset of

0and a length of64spans the first64 - 0 = 64bytes offile_a. - A global offset of

64and a length of64spans the last80 - 64 = 16bytes offile_a, all32 - 0 = 32bytes offile_b, and the first16 - 0 = 16bytes offile_c. - A global offset of

128and a length of64spans the last32 - 16 = 16bytes offile_cand all32 - 0 = 32bytes offile_d.

The write method of a Storage instance accepts a byte string to write and a global offset to start writing to. It passes this global offset and the length of this byte string to the _intervals method, and then writes the byte string across the returned spanning file intervals. Similarly, the read method accepts a length of bytes to read and a global offset to start reading from. It passes these parameters to the _intervals method, reads the data across the returned spanning file intervals, and then returns this data concatenated together. For example:

| |

This prints True when run.

A StorageWrapper instance raises the level of abstraction. It presents a view of storage at the level of pieces instead of at the level of bytes. Because pieces follow zero-based indexing, piece i has a global offset of i * size in a completed torrent. When the client finishes downloading a piece, the StorageWrapper instance calls the write method of Storage to write its piece size bytes across its corresponding file intervals. Similarly, when a peer requests a piece from the client, the StorageWrapper instance calls the read method of Storage to read its piece size bytes across its corresponding file intervals.

But while the client is still downloading the torrent, the StorageWrapper instance can temporarily store a piece at an global offset that is smaller than its final global offset. It does this to avoid preallocating all the files belonging to the torrent on startup, since not all platforms support efficient preallocation through the truncate system call. If the client has downloaded only n pieces, then the StorageWrapper instance has allocated only n * size bytes on disk. Only once the client has downloaded all the pieces is each one stored at its final global offset.

For example, consider a torrent with just four pieces. Say the client downloads piece 3 first. StorageWrapper cannot write this piece to its final global offset just yet, and so it temporarily stores this piece at the final global offset of piece 0:

The client then downloads piece 1. StorageWrapper writes this piece directly to its final global offset:

The client then downloads piece 0. Piece 3 currently occupies its final global offset, and so StorageWrapper relocates this piece to the final global offset of piece 2, which is still missing. Once this is done, StorageWrapper writes piece 0 directly to its final global offset:

Finally, the client downloads piece 2. StorageWrapper relocates piece 3 to its final global offset, and then writes piece 2 directly to its own final global offset:

At this point, StorageWrapper has written each piece to its final global offset, and the torrent is complete.

Other modules in the application interact with the StorageWrapper, because such modules refer to pieces, not file intervals. StorageWrapper delegating to its Storage instance as a design choice that simplifies its own implementation. Moreover, the StorageWrapper class exemplifies encapsulation: No other modules even need to know that pieces are composed of file intervals, or even that StorageWrapper delegates to an underlying Storage instance.

The message processor

The logic that processes messages from the network is split across the Encrypter and Connecter classes. Similar to the storage layer, this creates two levels of abstraction to simplify the code. An Encrypter instance presents a low level of abstraction, treating data as bytes. A Connecter instance presents a high level of abstraction, treating data as complete messages. Again, let’s consider each in turn.

An Encrypter instance contains a state machine that endlessly reads bytes from a peer until its connection closes. Because the bytes constituting a single message may trickle in, the Encrypter instance buffers received bytes until it can construct a full message.

The following code implements the state machine. It calls next_func with the contents of the buffer once it has accumulated next_len bytes:

| |

The state machine first negotiates the connection handshake which reads the protocol and unique identifier of the peer. It then simply alternates between assigning read_len and read_message to next_func:

| |

Every message is prefixed with its length. Once the buffer accumulates four bytes, method read_len decodes them as an integer specifying the length of the following message. Then once the buffer accumulates this number of bytes, method read_message passes them as a complete message to method got_message of its Connecter instance. This process then repeats itself.

Method got_message of Connecter processes the complete message sent by the peer. It extracts the first byte of the message as msg_type. The value of this byte determines how it should interpret the remaining bytes of the message. After method got_message extracts any message fields from these bytes, it passes these fields to the appropriate method of its Download or Upload instance. These instances contain the download and upload state of the peer. They belong to the Connection instance for the peer, called conn:

| |

Equally simple conditional branches direct request and cancel messages to the Uploader instance, and piece messages to the Downloader instance. If the msg_type field is unrecognized, then the client disconnects from the peer.

Data sent to the peer also respects these two levels of abstraction. For example, the Connecter module defines methods to send every type of message to a peer:

| |

Although the references to self.connection are slightly confusing, each method is calling the send_message method defined in the Encrypter module. Note that the argument to send_message is a complete message that method got_message of Connecter can decode. This is consistent with the interface between Encrypter and Connecter treating data as complete messages.

The called send_message method in the Encrypter module is defined as:

| |

Here the Encrypter sends the message length, followed by the message itself, over the connection established by the RawServer instance. Note that these two data values are exactly what the Encrypter belonging to the peer will read, using its read_len and read_message methods. This is consistent with the interface between Encrypter and RawServer treating data as bytes.

Again we have two levels of abstraction, where Connector treats data as complete messages, and Encrypter treats data as bytes. Modules in the client that refer to and process complete messages use the Connector class, while the Encrypter class is used exclusively when reading from a socket.

The networking engine

The RawServer module, which implements the reactor pattern, uses a system call that uses a set of file descriptors, a set of events for each socket, and an optional timeout value. Each file descriptor specifies a socket. The client is always interested in reading data from sockets, and so it sets the read event on each file descriptor. If the client has data enqueued for sending over a socket, then it sets the write event on that socket’s file descriptor. If the read event is set and data is waiting to be read from the socket, or if the write event is set and the socket’s underlying TCP/IP buffer isn’t full, then the system call returns its file descriptor. If neither condition is satisfied, then the system call returns after the specified timeout elapses. By not blocking indefinitely, the RawServer instance can run any tasks that are scheduled later.

The problem is that Python exposes two such system calls, called select and poll, with very different interfaces. The select system call is a single method with the following signature:

| |

Above, rlist is a list of file descriptors the client is interested in reading, wlist is a list of file descriptors that the client is interested in writing, xlist is ignored, and the timeout value comes last. This method returns three lists of ready file descriptors, where the first list contains file descriptors that are ready for reading, and the second list contains file descriptors that are ready for writing. Each returned list is a subset of its respective input parameter. If both returned lists are empty, then the timeout expired.

But the poll system call has a different interface. Python implements it as a polling object with multiple methods. A client registers file descriptors with this polling object by calling its register method:

| |

The eventmask parameter specifies what events the polling implementation should monitor on the file descriptor. POLLIN specifies reading, POLLOUT specifies writing, and the bitwise combination POLLIN | POLLOUT specifies both reading and writing. A client unregisters a file descriptor by passing it to the unregister method of the polling object.

After registering file descriptors for reading or writing, the client calls the polling object’s poll method:

| |

This method blocks until at least one registered file descriptor is ready for reading or writing, or until the given timeout expires. It returns a list of ready file descriptor and event pairings. In each pair, the event is POLLIN if the file descriptor is ready for reading, and the event is POLLOUT if the file descriptor is ready for writing. A file descriptor that is ready for both reading and writing appears twice in the returned list. If the timeout expired, then this list is empty.

A client should prefer using poll over select, as its implementation is more efficient. But the poll system call is not available on all operating systems. In this case, the client must fall back on the select system call. To implement this without severely complicating the logic of RawServer, the client has a selectpoll module that defines its own polling object. This polling object uses select, but it has the same interface as the polling object using poll. Class RawServer can therefore use either one without any changes.

The polling object of the selectpoll module has two lists named rlist and wlist. These contain the file descriptors that the client is interested in reading from and writing to, respectively. Its register method has the same signature as that belonging to the polling object for poll. When the client calls this method, it updates the membership of the given file descriptor in rlist and wlist accordingly:

| |

The polling object in selectpoll also has an unregister method that accepts a file descriptor to no longer monitor events for. Again, this method has the same signature as that belonging to the polling object for poll. It removes the given file descriptor from both rlist and wlist.

Finally, this polling object has a poll method that accepts a timeout value. It calls select with rlist and wlist, as well as with the given timeout value. It merges the lists returned by select into a single list that contains file descriptor and event pairings, and then returns this list to the client. Again, this method has the same signature as that belonging to the polling object for poll:

| |

The selectpoll module names this polling object poll. Now RawServer.py contains:

| |

The RawServer module tries to import the polling object for poll from the select module in the Python standard library. If the operating system does not support poll, then this object is unavailable, and the Python interpreter raises an ImportError. This causes the RawServer module to import the polling object from the selectpoll module instead.

The code that follows in RawServer is unaware of and unconcerned with which polling object it is using. That detail has been abstracted away. Moreover the client that uses the RawServer instance is similarly unaware and unconcerend with the chosen polling implementation.

If you’ve read the chapter on design patterns, you might recognize this as an example of the adapter pattern. The selectpoll module adapts the select system call to the interface of the polling object using the poll system call.

Bit field instances

When downloading a torrent with n pieces, the client maintains a bit field with n bits. The client sets bit i if it has downloaded and verified piece i.

When the client connects to a peer, it sends this bit field to the peer as part of the handshake sequence. The peer then reciprocates by sending its own bit field of pieces that it has. When the peer later completes downloading a piece, it sends a have message to the client, which sets the corresponding bit in that peer’s bit field. The client therefore knows which pieces each of its peers have. As described earlier, from this the client can compute the availability of each piece, and prioritize downloading the rarest pieces from its peers.

The Bitfield class lets us easily query and manipulate such a bit field. After creating a Bitfield instance with a given number of bits, the client can set or clear a bit by assigning True or False to a given index. The complete() method of a Bitfield instance returns True only if all of its bits are set. This means that the Bitfield instance belongs to a seed. If it is the client’s own Bitfield instance, then the client has completed downloading the torrent. Finally, the tostring() method of a Bitfield instance returns a compact byte string representation. The client delivers this representation of its own bit field to a peer during the handshake sequence. When the client receives such a byte string from another peer, it can initialize the bits of that peer’s Bitfield instance with that string.

For example, the following code initializes a Bitfield so that 6 of its 8 bits are set. Consequently, its complete() method returns False. After the code sets the two cleared bits, its complete() method returns True:

| |

When run, this prints:

| |

Similar to the Request class from the chapter on object-oriented design, the Bitfield class provides meaningful operations belonging to the problem domain. Requiring the client to query or manipulate a byte string directly is tedious and binds the client to the implementation domain. For example, determining how many pieces the client is missing requires counting the number of cleared bits in its own byte string. And a peer delivering a have message with a piece index requires setting the corresponding bit in that peer’s byte string. These tasks require bitwise operations, including shifting and masking. Using the Bitfield class instead greatly simplifies the code.

Decomposition

Dividing your program into modules, classes, functions, and even statements are all examples of decomposition. Therefore any reasonable program has some degree of decomposition. But below we explore a very nuanced instance of decomposition in the BitTorrent client, generated by decomposition in the BitTorrent protocol itself.

Peer state

A client uploads data to and downloads data from a given peer over the same socket, but the BitTorrent protocol defines them as independent processes. The client will upload to a peer only if that peer is interested in pieces that the client has, and if the client is not choking that peer. Likewise, the client can download from a peer only if it is interested in pieces that the peer has, and if that peer is not choking the client.

The design of the mainline client recognizes this independence. Every connection to a peer has an instance of the Upload class and an instance of the Download class. These instances encapsulate the state and logic for uploading to and downloading from that peer.

The Upload class contains:

- A boolean named

chokedthat specifies whether the client is choking the peer. - A boolean named

interestedthat specifies whether the peer is interested in pieces that the client has. - A list named

bufferthat contains outstanding requests by the peer for data that the client has. The client processes the next outstanding request onceRawServerhas written all enqueued data to that peer’s socket. - An object named

measurethat measures the upload rate to the peer. When the client is a seed, it uses these rates to unchoke the peers that it can upload to the fastest, excluding the optimistically unchoked peer.

The Download class contains:

- A boolean named

chokedthat specifies whether the peer is choking the client. - A boolean named

interestedthat specifies whether the client is interested in pieces that the peer has. - A

Bitfieldinstance namedhavethat specifies which pieces the peer has. The client initializes it during the handshake, and updates it with every have message from the peer. - A list named

active_requeststhat contains outstanding requests by the client for data that the peer has. When the peer returns data, the client removes its corresponding request from this list. The client clears this buffer whenever the peer chokes it, thereby cancelling all of the client’s outstanding requests. - An object named

measurethat measures the download rate from the peer. When the client is a peer, it uses these rates to unchoke the peers that it can download from the fastest, excluding the optimistically unchoked peer.

The implementation of class Upload is quite simple. This is because a peer dictates most of the state of its corresponding Upload instance. The client specifies only the choked value of each instance. For example, the following methods from class Upload process uninterested and interested messages received from a peer:

| |

When the client receives an uninterested message from a peer, method got_not_interested clears the buffer of outstanding requests by that peer, and then chokes it. When the client receives an interested message from a peer, method got_interested notifies the Choker instance. This in turn may later unchoke that peer, allowing it to again request pieces belonging to the client.

The code in the Download class is significantly more complicated than that in the Upload class. This is because a Download instance must constantly request pieces from a peer that is not choking the client. The PiecePicker instance decides which pieces it requests. Furthermore, the client requests intervals of pieces belonging to its peers. By simultaneously downloading different intervals of a given piece from multiple peers, the client completes that piece faster. This, in turn, reduces the time until it can upload that piece to its own peers. This improves the health of the torrent, but complicates the implementation of the Download class.

Finally, when the client has only a few pieces left to download, each Download instance enters endgame mode. The client aggressively downloads these last pieces from as many peers as possible so that these pieces do not “trickle in.” This again increases complexity, but again the design contains this complexity to the Download class. The Upload class remains simple.

Summary

In this chapter, we examined how the original BitTorrent client employed robust design to make its code more reusable and less complex. Features of its design include efficient use of loose coupling, abstraction, decomposition, and encapsulation. Seek to incorporate these principles of robust design into your own code.